Edward Steichen in Vogue Arts Culture Smithsonian

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Marion-Morehouse-and-unidentified-model-wearing-dresses-Edward-Steichen-631.jpg)

For the photographers who followed him, Edward Steichen left a creative wake of Mozartean dimensions. There was not much that he didn't do, and do extraordinarily well. Landscapes, architecture, theater and trip the light fantastic toe, state of war photography—all appear in his portfolio.

Born in 1879 in Grand duchy of luxembourg, Steichen came with his family to the Usa in 1881 and started in photography at age 16, when the medium itself was still young. In 1900, a critic reviewing some of his portraits wrote admiringly that Steichen "is not satisfied showing united states of america how a person looks, but how he thinks a person should look." During his long career, he was a gallery partner with the bang-up photography promoter Alfred Stieglitz. He won an Academy Accolade in 1945 for his documentary film of the naval state of war in the Pacific, The Fighting Lady. He became the first director of photography at the Museum of Modernistic Art in New York City and created the famous "Family unit of Human" exhibition in 1955.

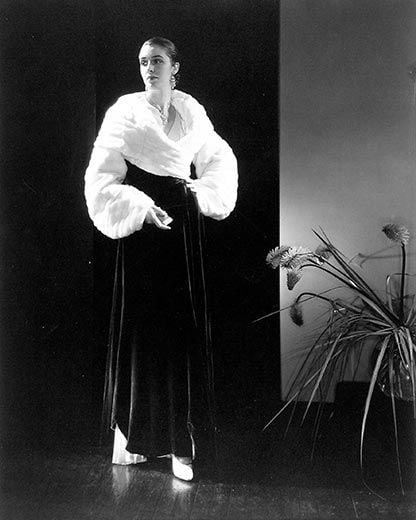

Though Steichen didn't invent mode photography, an argument tin be made that he created the template for the mod manner lensman. A new volume, Edward Steichen in High Fashion: The Condé Nast Years 1923-1937, and an exhibit through May 3 at the International Middle of Photography in New York make that argument with verve. Though expensively dressed women had attracted other photographers (notably the very immature Jacques-Henri Lartigue in Paris), Steichen set an enduring standard. "Steichen was a perfectionist," says Howard Schatz, a style photographer whose portraits of actors appear in Vanity Fair. "His precise centre for lighting and design makes his pictures from the '20s and '30s, though conspicuously of their time, still much admired by mode photographers today."

Steichen spent the first years of the 20th century in Paris, pursuing parallel careers as an art photographer and painter. Those callings, not to mention the sumptuous urban center itself, would have led his eye toward women, both undressed and very well dressed. In 1907, he made a photograph of two ladies in dazzling white dresses getting into a wagon at the Longchamp racetrack—an early bespeak that he had an instinct for couture. 4 years subsequently, he was assigned by the French magazine Art et Décoration to produce pictures of dresses by the Parisian designer Paul Poiret. Every bit William Ewing, director of the Musée de fifty'Elysée, puts it in an essay in the book, "Whatsoever sophisticated American in Paris with the visual curiosity of Steichen would have been hard-pressed not to pay attention to this domain of publishing." But his success as a fine art lensman outweighed his interest in the more commercial realm of fashion magazines, and he didn't make some other fashion photograph for more than than a decade.

Then he went through "a bad and expensive divorce," says another of the book's essayists, Carol Squiers, a curator at the International Centre of Photography. By 1922, when Steichen was 43, he was undergoing what we at present phone call a midlife crisis. He had, every bit Ewing puts it, "serious misgivings near his talents with the brush," and Squiers writes that he told fellow photographer Paul Strand that he was "sick and tired of being poor." He needed something to renew his energies and, non incidentally, a means of making his pension and child-back up payments.

Dorsum in New York, he was invited to a dejeuner that provided a remedy. The invitation came from Frank Crowninshield, the editor of Vanity Off-white, and Condé Nast, the publisher of both that magazine and Vogue, whose married woman and girl Steichen had photographed while in Paris. It was Nast who offered him the job of chief photographer for Vanity Off-white, which meant, substantially, house portraitist. But regular style work for Vogue was also part of the deal, and Steichen gladly accepted it.

At that magazine, he would take the place of the famous Businesswoman Adolphe de Meyer, who had been lured to Harper'southward Boutique. Though de Meyer was fashion photography's start star, Steichen before long became its well-nigh luminous.

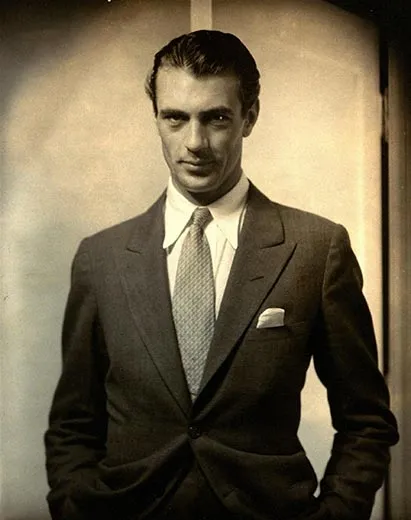

His portraits for Vanity Fair brought him new fame, at least in office because of the condition of such glory subjects as Gloria Swanson (whom he draped with an evocative veil of black lace) and a formidably handsome Gary Cooper. But on his Faddy assignments Steichen produced pictures every bit meticulously conceived every bit whatever painting by Gainsborough or Sargent—even though he needed to fill page afterwards page, calendar month after month. "Condé Nast extracted every final ounce of work from him," Squiers told me in an interview. Steichen "was a ane-man industry for the magazines, so he had to work quickly. But he had a not bad heart for where everything should be."

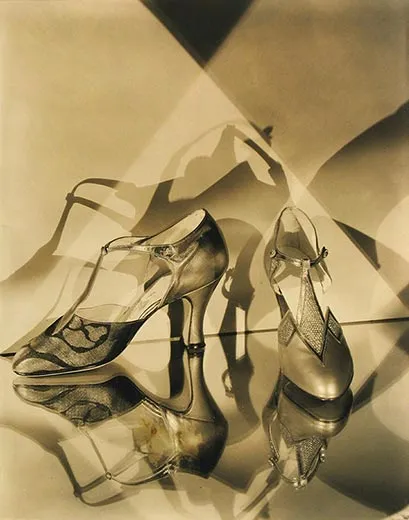

Steichen's corner-to-corner attentiveness, coupled with his painterly training, immune him to make fashion pictures that ranged in way from archetype 19th-century illustrations to Art Nouveau and Fine art Deco. "He was designing with his camera," Squiers says, "and after starting out as a [soft-focus] pictorialist, he brought sharp focus to acquit and had a tremendous effect on the field."

Typical of his piece of work is a 1933 picture of a model wearing a patterned dress by a designer named Cheney. Steichen poses her in front end of a two-tone groundwork covered with calligraphic curves that echo the dress, so adds a white chapeau, scarf and gloves, a bentwood chair and tulips—all of which brand a composition reminiscent of a Matisse painting. But he too used motion picture conventions to brand even studio photographs—which are by definition artificial—appear to be life at its most enviable. If two women and a homo sat at a well-appointed dinner table, Steichen made sure that function of another tabular array, gear up with equal lavishness, appeared behind them, turning the studio into a fine restaurant in which the black dresses and tuxedo found their proper context.

In 1937, Steichen left Condé Nast and, according to Squiers, spent the next few years raising delphiniums. (He had become an avid and accomplished gardener in France.) Later on the The states entered World State of war Ii, he put on the uniform of a Navy officer and devoted his talents to the war effort. He never returned to photographing clothes, though he kept taking pictures almost until his expiry, on March 25, 1973, two days short of his 94th birthday.

Later on the war, a new generation of fashion photographers, most notably Richard Avedon, adopted smaller cameras and faster film, and they began to leave their studios and urge models to movement naturally rather than pose. The advisedly staged black-and-white Steichen pictures that delighted prewar readers of Vogue more often than not gave way to color and spontaneity. But as Edward Steichen in Loftier Way proves, his pictures retain their power to please.

Owen Edwards is a frequent contributor to Smithsonian.

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/edward-steichen-in-vogue-125189608/